What is popularly called parental alienation is better referred to clinically as a childhood relational trauma, in which the attachment relationships a child has with their parents, are maladapted due to the impact of stress in the family system. Relational trauma is conceptualised as abuse which happens in a close relationship and when that is caused by a caregiver, it can be conceptualised as a childhood relational trauma (Dugal; Bigras; Godbout & Bélanger, C. 2016),

Attachment maladaptations are a way of surviving trauma, they enable a child to continue to survive in a changing world without dissociation (Adshead & Fonagy, 2012; Fisher, 2017). They occur in divorce and separation when the child enters into a double bind situation which they cannot escape from.

A double bind situation occurs between two people who have emotional and psychological bonds which are meaningful, the double bind occurs when the person in that relationship with more power, creates a contradictory condition which the person with the lesser power is obligated to conform to. (Bateson, Healy & Wakeson, 1956).The final condition to create a double bind situation, is to ensure that the person with lesser power, cannot escape their dependency upon the creator of the double bind. Hence, a child who finds themselves in a situation where a parent they are depedent upon, is giving contradictory messages – ie ‘go to your father’s house/if you go to your father’s house I may not be here when you get back’ will withdraw from their father in order to conform to the secondary message in the double bind situation.

The reason that a child will conform to the secondary message is the power that the manipulating parent has over them and the threat of abandonment that the child feels, should they not conform. In such circumstances. The attachment maladaptation is one in which the child defends against their own awareness of the injustice of the double bind, exchanging awareness of their experience of the manipulative parent for denial of what is being done and projection of the split off awareness onto the parent in the rejected position. This mental shift is called ‘identification with the aggressor‘ in the psychological literature and it is the reason why children who are being abused and who have witnessed the abuse of the rejected parent, will align with the abuser rather than the victim who is being rejected.

Working with children who have the defence of identification with the aggressor requires a particular approach in order to enable the child to withdraw the projection and resolve the denial of awareness of the harm which is being caused to them. Because the alignment with the aggressor is a defence, it is only a partial alignment, although it looks complete in that the child will mimic the aggressors behaviour, often to the point of cruelty towards the parent in the rejected position.

In working clinically, with children who show this pattern of behaviour however, it is clear that they display different parts of self at different times and in different circumstances. These parts of self, which are not dissociative parts but caused by ego splits, may manifest unpredicatably, meaning that being aware of how people with ego splitting behave is an important part of being able to help alientated children. Understanding ego splitting means recognising that the defence causes splits in the sense of self, meaning that part of the self is identifying with the aggressor and another part of self is rendered unconscious. There may be more parts of self involved because parents who manipulate their children through fear and anxiety, do not just begin that process during divorce or separation, it is a pattern of relational behaviour which is often well established in the family system.

Ego Splitting

Clinical practice with alienated children demonstrates that ego splitting is the core defence seen in the child who is being pressured in the family system by one or both parents. (Woodall, 2023). Ego splitting is understood in the trauma literature, as a process by which internal conflicts are managed in situations where they cannot be resolved (Fisher, 2017). In divorce or separation, when a parent is frightening or frightened and thus, in the felt sense, feels out of control to the child, splitting is a way of defending against the terror being caused in the inter-psychic relationship. Splitting is a well understood defensive process in which the child divides the self (subject) into parts, the most usual of which are good self/bad self, the disavowed parts of self, are then projected onto the parent (object), who is in the rejected position. The signs that a child is splitting is the appearance of idealisation of the aligned parent and the corresponding demonisation of the parent in the rejected position. When this occurs it shows that the child is suffering from ego splitting as a defence against something in the system. As ego splitting causes unstable relationships and is a core symptom of borderline personality disorder, (Gould; Prentice & Ainslie 1996)the risk to the child is evident.

The by-product of ego splitting in the child, is the regulation of the frightened or frightening parent, who is soothed by the child’s alignment with their internal experience. When the child experiences this regulation of the parent, the drive to repeat it begins, so that the system in which the child is living, remains stable. This is an attachment maladaptation which is frequently seen in clinical practice with children who align and reject and it signals a trauma based response in the child caused by ego splitting. In this respect, alienation of the child can be understood to be the onset of a false defensive self, which alienates the child from their own true, integrated sense of self.

Treatment

Working with children who are alienated therefore requires understanding of the child’s internal sense of self and the capacity to organise the outside world in such a way that enables resolution. In situations where a child is being controlled by a frightened or frightening parent, the control element must be addressed first to free the child from the drive to regulate that parent.

(NB: frightened parents can control a child through anxiety, frightening parents control a child through more visible patterns of behaviour, both can be said to be coercion, which means to persuade someone to do something by threat or by force).

The stepwise approach to treatment is therefore –

a) the double bind position that the child is in, must be resolved BEFORE the child is required to change their behaviours in any way, if it is not, the child will not make the shift from the defended split self to the integrated authentic self.

b)working at a deeply attuned level with an alienated child is the fundamental requirement of anyone who is going to resolve the ego splitting which causes the problem. This is because the child who has already maladapted their behaviours due to divorce, is highly likely to suffer from either hyper mentalisation in the relationship with the influencing parent or hypo mentalisation. Hyper mentalisation refers to over thinking, in which a parent ruminates about the intentions of the relationship the child has with their other parent, hypomentalisation, refers to an inability in that parent to understand that the mind of the child is different to their own. Both of these states of mind in parents can cause ego splitting in the child as a defence against a double bind.

What this means is that the external conditions the child is in, must be addressed and the child must be protected from the double bind position BEFORE anyone attempts to resolve the ego splitting in the child and when the attempt to resolve ego splitting begins, it must attune to the exact presentation of the child and be prepared to move with the changes which occur moment by moment.

It is my view that until now, the way in which an alienated child shifts position and presents different aspects of self, has not been recognised for what it really is, which is ego splitting as a response to coercive control strategies employed by a parent. It is only in working closely with alienated children that this behavioural pattern can be observed and compared across the recovery process. When it is, the internal state of mind of the child who has experienced coercive control, can be integrated and the child can be protected from further efforts by a parent to cause the child to once again align. This work is about giving a child who has experienced coercive control by a primary caregiver, the awareness of self and other which protects against an internalised pattern of behaviour which causes vulnerability to future relationships which feature patterns of control. Ultimately, this is about breaking cyclical patterns of childhood relational trauma which protect children in future generations.

References

Adshead, G. and Fonagy, P. (2012). ‘How does Psychotherapy Work? The Self and its Disorders’. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 18(4): 242–249

Bateson, G., Jackson, D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J. “Towards a Theory of Schizophrenia.” 1956.

Dugal, C., Bigras, N., Godbout, N., & Bélanger, C. (2016). Childhood Interpersonal Trauma and its Repercussions in Adulthood: An Analysis of Psychological and Interpersonal Sequelae. InTech. doi: 10.5772/64476 2.

Gould, J. R.; Prentice, N. M.; Ainslie, R. C. (1996). “The splitting index: construction of a scale measuring the defense mechanism of splitting”. Journal of Personality Assessment. 66 (2): 414–430.

Woodall K (2023). ‘Childhood relational trauma in Children of divorce and separation’ Family Separation Clinic Briefing Paper.

Family Separation Clinic News

The Clinic is now fully engaged with the development in the field of childhood relational trauma which will offer parents and professionals new resources to support children and families in divorce and separation.

The Clinic has limited capacity as a result and can only accept instructions in the High Courts of England and Wales, Republic of Ireland and Hong Kong on a very limited basis.

The Clinic occasionally opens booking for individual consultations, please see our website for details of how to book – http://www.familyseparationclinic.co.uk

Two new books will be available which support the work under development, the first is a handbook of therapeutic parenting written by Karen Woodall, the second is a handbook of clinical practice written by Nick Woodall and Karen Woodall. Details of both will be available soon.

The Clinic is currently involved in pathfinder partnerships with Local Authorities, developing and evaluating the Clinic’s structural interventions in statutory settings. Details of outcomes will be made available in due course. Other evaluation work is ongoing.

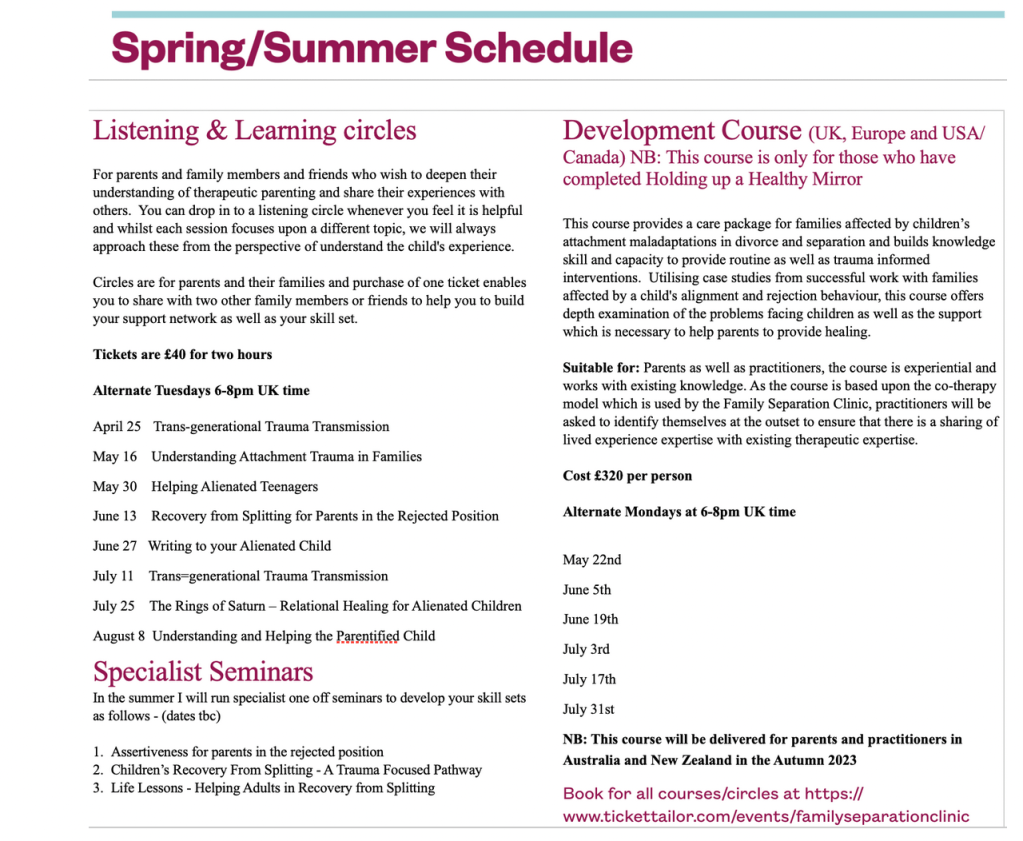

Listening Circles Continue to be delivered by Karen Woodall the schedule for the summer circles is as follows –

June 7th (rearranged date) – Therapeutic Parenting for Alienated Teens

Further dates are here (specialist seminars will be announced shortly).