In situations of relational coercion following parental separation, children may be driven into a specific attachment posture that is not well recognised in mainstream clinical literature (Main & Solomon, 1990; Liotti, 2004). This posture is characterised by stillness, inhibition of protest, heightened watchfulness and collapsed autonomy, while remaining rigidly oriented toward the attachment figure who is experienced as a source of threat (Main & Hesse, 1990; Schauer & Elbert, 2010). Developmental and trauma research describes this as a form of disorganised or immobilised attachment, emerging when a child faces what Main and Solomon termed “fright without solution” (Main & Solomon, 1990). In this state, the child does not flee, does not fight, and does not securely attach, instead becoming immobilised in a fearful orientation, a posture best understood as biologically encoded submission in the service of survival (Porges, 2011; van der Kolk, 2014).

When a child becomes held in this immobilised attachment posture, the impact does not remain confined to the child alone as the parent in the rejected position is often drawn into a parallel relational position, one that is similarly characterised by waiting, appeasing, inhibited self-expression, and the suspension of ordinary parental agency (Bowlby, 1980; Shear, 2012). Rather than being able to move freely, respond spontaneously, or maintain a confident parental stance, the rejected parent finds themselves becoming increasingly still, careful, and oriented around the child’s emotional field (Feldman, 2007; Schore, 2001).

This mirrored immobilisation does not arise from weakness but from the biological pull of the attachment system itself. Faced with the loss of contact and the threat of permanent relational rupture, the parent’s nervous system shifts into a state of frozen orientation, which looks like a posture of quiet, watchful devotion that closely parallels the child’s own immobilised attachment stance (Bowlby, 1980; Porges, 2011). When both child and rejected parent become held in these parallel states of immobilised orientation, a distinct relational field begins to organise itself around the separation (Herman, 1992; Liotti, 2004). This field is not simply the absence of contact, nor merely the presence of conflict, but a trauma-organised attachment environment in which movement, repair, and reciprocal relating become progressively inhibited (Schauer & Elbert, 2010). The child remains biologically oriented toward the controlling attachment figure, while the rejected parent becomes biologically oriented toward the lost child (Bowlby, 1980). Both are held in states of frozen devotion, watchful waiting, and suspended agency. This mutual immobilisation creates what may be understood as a stagnant attachment field, which is a relational environment in which attachment remains activated but cannot move, settle, or repair.

The stagnant attachment field does not dissolve simply because contact is reduced or ended. Attachment is not a cognitive preference but a biological survival system (Bowlby, 1969; Porges, 2011), and once it has been organised around threat, loss, and immobilisation, it continues to operate long after the external conditions have changed (Shear, 2012; van der Kolk, 2014).

Remaining within a stagnant attachment field carries a quiet but cumulative cost. Over time, the prolonged suspension of agency, movement, and reciprocal relating begins to shape a parent’s emotional life, identity, and bodily health. Many parents describe living in a state of chronic alertness, low-grade grief, and internal waiting, as though part of the self remains paused in an unfinished conversation. This ongoing biological emergency response is associated with fatigue, anxiety, low mood, immune vulnerability, and a gradual narrowing of life space (McEwen, 1998; van der Kolk, 2014; Shear, 2012).

When professionals encounter parents who are held within a stagnant attachment field, what they often see is not the underlying biological immobilisation, but its surface expressions. These may include persistent preoccupation with the child, heightened emotional intensity, difficulty “moving on,” repeated help-seeking, and a continued orientation toward repair. Without an attachment-informed and trauma-informed lens, these behaviours are frequently mislabelled as obsessional, dependent, intrusive, or emotionally dysregulated. In some cases, the parent’s frozen devotion is misinterpreted as evidence that they themselves are the cause of the child’s rejection. This represents a profound clinical error (Herman, 1992; Stark, 2007; Liotti, 2004).

Healing does not require the parent to abandon love, nor to deny longing, nor to “let go” of the child in any emotional sense. What it does require is the reorganisation of the attachment field itself. When a parent begins to restore agency, relational movement, and embodied self-orientation, the stagnant attachment field can gradually loosen its hold. This process is not a cognitive decision but a biological re-patterning: the nervous system is supported to step out of immobilised waiting and back into living connection, creative movement, and self-directed meaning (Porges, 2011; Ogden et al., 2006; Herman, 1992).

Standing up from kneeling is not a dramatic act of emotional withdrawal, nor a declaration of independence from the child. It is a gradual, embodied return to upright relational living. Parents begin to notice small but significant shifts: breathing becomes deeper, daily life expands, decision-making returns, and moments of genuine pleasure re-enter the body. The nervous system slowly re-orients from constant watchful waiting toward present-moment engagement, creative movement, and reciprocal relationships that are safe and nourishing (Ogden et al., 2006; van der Kolk, 2014). From this upright stance, parents are no longer suspended in a posture of silent devotion. Instead, they become rooted in their own lives while remaining open, emotionally available, and capable of responding when the child has a strong enough ego to begin to follow the attachment drive to reconnect. Uprightness restores dignity, vitality, and agency, not in opposition to love, but as the foundational necessity to parenting an attachment-traumatised child.

For parents living within a stagnant attachment field, healing is not a demand, an instruction, or a requirement to “move on.” It is an invitation back into life which honours the reality of love while also recognising the cost of remaining immobilised by loss. Standing up from a kneeling attachment posture is a compassionate act, first toward the self, then toward the body, and ultimately toward the child. This is because it restores the parent to a state of embodied presence rather than frozen devotion. From this upright, regulated stance, parents are more able to offer steady availability, clear boundaries, and relational safety. This is what we call Living in the Lighthouse Position, which is a form of healing which does not close the door to the child but which opens the door to life, dignity, and sustainable love and eventual repair of the attachment harm which has been caused.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. Basic Books.

Feldman, R. (2007). Parent–infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing. Infant Behavior & Development, 30, 44–56.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Liotti, G. (2004). Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(1), 3–25.

Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences and infant disorganized attachment. In M. Greenberg et al. (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years (pp. 161–182). University of Chicago Press.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying disorganized/disoriented attachment. In M. Greenberg et al. (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years (pp. 121–160). University of Chicago Press.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 171–179.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body. Norton.

Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory. Norton.

Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 218(2), 109–127.

Schore, A. N. (2001). Effects of early relational trauma. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 201–269.

Shear, M. K. (2015). Complicated grief. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1315618.

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control. Oxford University Press.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score. Viking.

News from the Family Separation Clinic

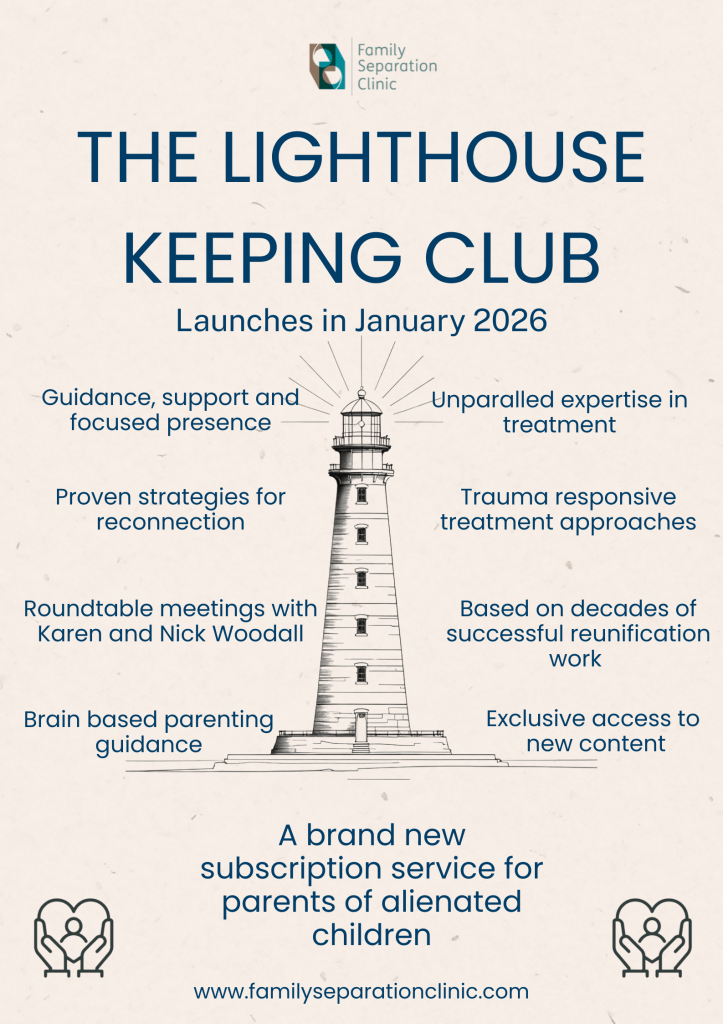

The Lighthouse Keeping Club is a new service from the Family Separation Clinic which provides support, connection, guidance and presence for parents who have children affected by this attachment trauma. The Lighthouse Keeping Club will offer regular connection with the expertise at the Family Separation Clinic, including seminars and events with Karen and Nick Woodall. The Lighthouse Keeping Club is for parents with children of all ages and at all stages in the journey of this attachment trauma, including the post reconnection stage in which much of the work of healing the attachment harms takes place. The Lighthouse Keeping Club will cost £25 /$33 per month and will give access to discounts on training and therapy groups. This service is designed to offer low cost access to the services of the Family Separation Clinic and runs alongside our watch on demand service which is at www.fscparenting.com

Therapy Groups

Our therapy groups are facilitated by Karen Woodall and are designed for those parents who want to work at a deeper level on recovery from attachment harm. We are offering three options in the Winter term 2026 –

The Lighthouse Keeping Group – Northern Hemisphere

The Lighthouse Keeping Group – Southern Hemisphere

Mothers Therapeutic Support Group

You can find out more and book below

New Books

We are now in the publishing process for The Journey of the Alienated Child with a major publishing house and will announce the details of this and two further new books for 2026 shortly.

Thank you

To every parent who has trusted us to help with understanding and treating this transgenerational attachment trauma in 2025. We have heard from so many of you with positive news about reconnection and repair using the Lighthouse Keeping approach.

Everything we do at the Family Separation Clinic is in service to building and supporting healthy family life and all of the profits from our work go back into research, development and service delivery.

We are profoundly grateful too, for the ongoing investment support which enables us to create new services, write books and develop new routes to treatment of this family attachment trauma. Recognition of our work through this support, means that we can continue to help you to help and heal your children for many years to come.

We look forward to working with you in 2026

Karen and Nick Woodall

Family Separation Clinic, London.

30.1.2025