Parentification is an attachment trauma and describes the way in which a child has maladapted their attachment relationships so that they can regulate a parent who is using them to gratify their own emotional and psychological unmet needs. The harm which is caused to parentified children is recognised in the psychological literature in descriptions of family dynamics which show that there is a boundary dysfunction in the family subsystems, compelling a child to take on a parental or spousal role in the family.(Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, 1984b; Minuchin, 1977). These children will take executive roles withhin the family and will eschew their own developmental needs and enjoyment of life to fulfill the needs of a parent. The dependent behaviour of a parent, along with the dissolution of boundaries within the family system during times of crisis (such as family separation), leads to distortion of the parent/child relationship (Karpel, 1977).

Pathologically Parentified Children are bound, out of loyalty and concern to parental figures who unilaterally exploit them. –

Gregor Jurkovic

The problem for parentified children is that they become, over time, unable to actually experience their own feelings and can only experience those of the dependent parent. (Miller, 2007). This repeated accomodation, leads to the development of a false self, behind which the true feelings of the child are hidden (Winnicott, 1965b). In parentified children of divorce and separation, this false self is present in situations where children align strongly with a parent whose needs they have become used to taking care. In such circumstances, the rejection of the parent is a by product of that alignment.

Recognising the Parentified Child

The problem for parentified children is that they experience the attachment maladaptations they have made as being normal. This is why children who are strongly aligned with one parent and rejecting of the other will vehemently claim that their feelings as their own. The felt sense of the child who is parentified is that this way of life is normal, these feelings are normal and the outcome of feeling these feelings is that the world is safe and secure. This is because the maladaptations in the child’s attachment, are made so that the parent who is dependent upon them is regulated, through regulating a parent whose emotional and psychological expressions are chaotic and frightening, the child experiences order in the world and stability. The tragedy of the parentified child is that they are manipulated into disregarding their own needs in favour of meeting the needs of a parent. In fact many if not most, parentified children, do not even know that they have emotional and psychological needs of their own, growing up to become people pleasers, who feel empty if they are not carrying the burdens of others.

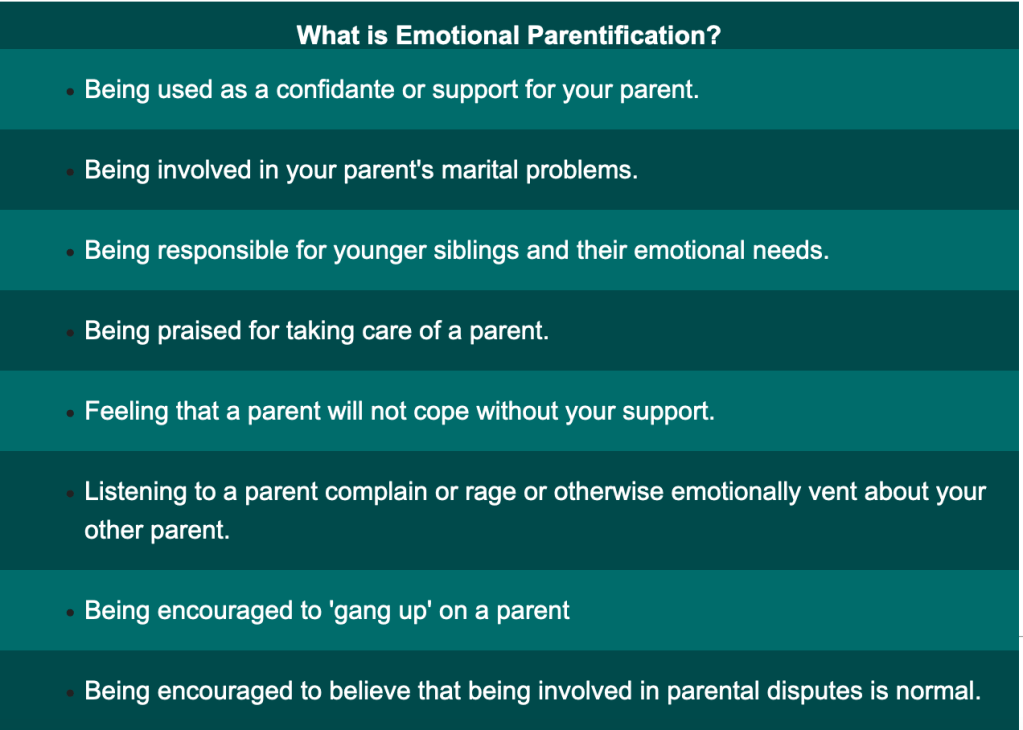

Parental Behaviours Causing Parentification

According to Karpel (1977), a failure of parenting causes the onset of parentification in children in situations where a parent’s needs were not met in childhood, leading to the exploitation of a child through systematic (though often subtle) manipulations, towards encouraging caregiving behaviour. Life events which may escalate this behaviour, include divorce and separation. When such events occur, a parent with unmet needs, will seduce the most willing, capable or vulnerable children within the family system, into the role of caretaker/parent and will reward the child in such circumstances, with the privilige of feeling elevated in the family system. (Locke & Newcomb, 2004). In this respect, the behaviour of the parent can be recognised as a form of grooming, in which the child is singled out to be the special child. The harm which is caused to parentified children by the behaviour of the manipulating parent, is significant and parentification, is often only one of the harmful behaviours seen when children align and reject.

Treating the Parentified Child in Divorce and Separation – Helping the Child to Know What They Do Not Know.

Treatment of parentification in children of divorce and separation relies upon structural interventions which recognise the harms that are caused when a parent seduces a child into a relationship which violates boundaries. Often, by the time a child reaches the point at which help can be given, the internalised experience of boundary violation will feel like a warm loving relationship and the child will, themselves, advocate for the maintenance of this dynamic, arguing that they themselves have chosen this and that they are not being made to meet parental needs, they WANT to meet those needs. In this respect, parentified children can be seen to be contributing to their own psychological and emotional harm, denying themselves the opportunity to have their own needs met and explore the world on their own terms, in favour of remaining in a false self, defended state, in which their existence is focused upon regulating a parent whose own needs were not met in childhood. In this respect, the generational transmission of attachment trauma is manifested and the parentified child becomes host to the unresolved trauma, at risk of passing this on to their own children in their own experience of parenthood. (Miller, 1981). This is why intervention is necessary, especially in cases of severe parentification where a child’s emotional and psychological development is impacted. Interventing in such circumstances requires the Court to manage the framework for therapeutic work, which is delivered after findings of harm have been made.

Treatment of such attachment maladapations requires a combination of therapeutic modalities which are focused upon enabling the integration of the false self states of the parentified child over time. The structure of this input will vary from child to child but is focused upon the restoration of the child’s internal experience of self as being in need of adult support and unblocking the capacity to receive care from a parent.

References

Boszormenyi–Nagy, I., & Spark, G. M. (1984a). Invisible loyalties. New York:Brunner/Mazel, Inc. .

Boszormenyi–Nagy, I., & Spark, G. M. (1984b). Parentification. In I.Boszormenyi–Nagy & G. M. Spark (Eds.), Invisible loyalties (pp. 151–166).New York: Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

Jurkovic, G. J. (1997). Lost childhoods: The plight of the parentified child. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Karpel, M. A. (1977). Intrapsychic and interpersonal processes in the parentification of children. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Massachussetts, Amherst.

Locke, T. F., & Newcomb, M. (2004). Child Maltreatment, Parent Alcohol- and Drug-Related Problems, Polydrug Problems, and Parenting Practices: A Test of Gender Differences and Four Theoretical Perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 120-134.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965b). Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. In D. W. Winnicott (Ed.), The maturational processes and the facilitating environment:Studies in the theory of emotional development (pp. 140-152). Connecticut: International Universities Press, Inc.

Miller, A. (1981). Prisoners of childhood: The drama of the gifted child and the search for the true self. (R. Ward, Trans.). Basic Books.

March 7 – 19:00 -21:00 GMT

Introduction to Therapeutic Parenting Skills

This is an introductory session for parents who are new to therapeutic parenting. Using basic skills as a starter, we will explore how understanding the self as a therapeutic parent, changes the way that you signal your position to your child. Whilst this is an introductory session, all parents are encouraged to join this circle to build up shared momentum for knowledge and skills amongst rejected parents. This develops the capacity of the rejected parent community to assist other parents who are new to this experience.

Cost £40 – Family and friends can attend for the cost of one place.

Book Here

March 21 – 19:00-21:00

Helping the Parentified Child

Parentification is one of the key problems facing children who are manipulated in divorce and separation, it is a covert manipulation which can be difficult to spot, precisely because, as Dr Steve Miller always pointed out, it looks like a close and loving relationship.

There is no need to be helpless in the face of the parentified child however and, because the relational networks in the brain are constantly open to change, learning how to help the parentified child is a powerful tool to have at the ready for any parent who has been forced into the rejected position.

This circle will focus upon understanding how parentified children behave and how to operationalise strategies to help them.

Cost £40 – Family and friends can attend for the cost of one place.

Book Here

April 4 – 19:00-21:00

What is really happening when a child rejects a parent outright

The evidence is clear that a child who rejects a parent outright after divorce and separation, is not doing so because that parent is abusive. Instead, it is the parent to whom the child is aligned who is causing harm and it is the alignment we should be looking at because it is this which is abusive to the child. It is abusive because, even though it looks like love, it is a fear based response which is underpinned by the biological imperative to survive. In the framework of latent vulnerability, what we are seeing when a child aligns in this way, is a child who is already vulnerable in the parental relationship, succumbing to underlying disorganised attachments. This circle will explore the reality of what happens when a child rejects a parent and will focus on how therapeutic parenting can assist the child to recover.

Cost £40 – Family and friends can attend for the cost of one place.