One of the most hidden harms in our society is that which occurs in a small group of families where children maladapt their attachment behaviours as their parents go through a divorce or separation. Often portrayed as being about the contact that a child has with their parents or as high conflict between parents, close work with these families, shows that they often feature psychopathology in one of the parents, which is poorly understood and so not responded to effectively.By effectively I mean protecting the child first and making longer term decisions from a place where the child is safe from the harm they are suffering. My view is that if we spent more time in observing and detailing the internal dynamics of these families, we would both understand them better AND be able to respond more effectively. Doing both is, in my view, no longer something which can be delayed because failing to do one or both leads to the horrific outcome of the Sara Sharif case in the UK.

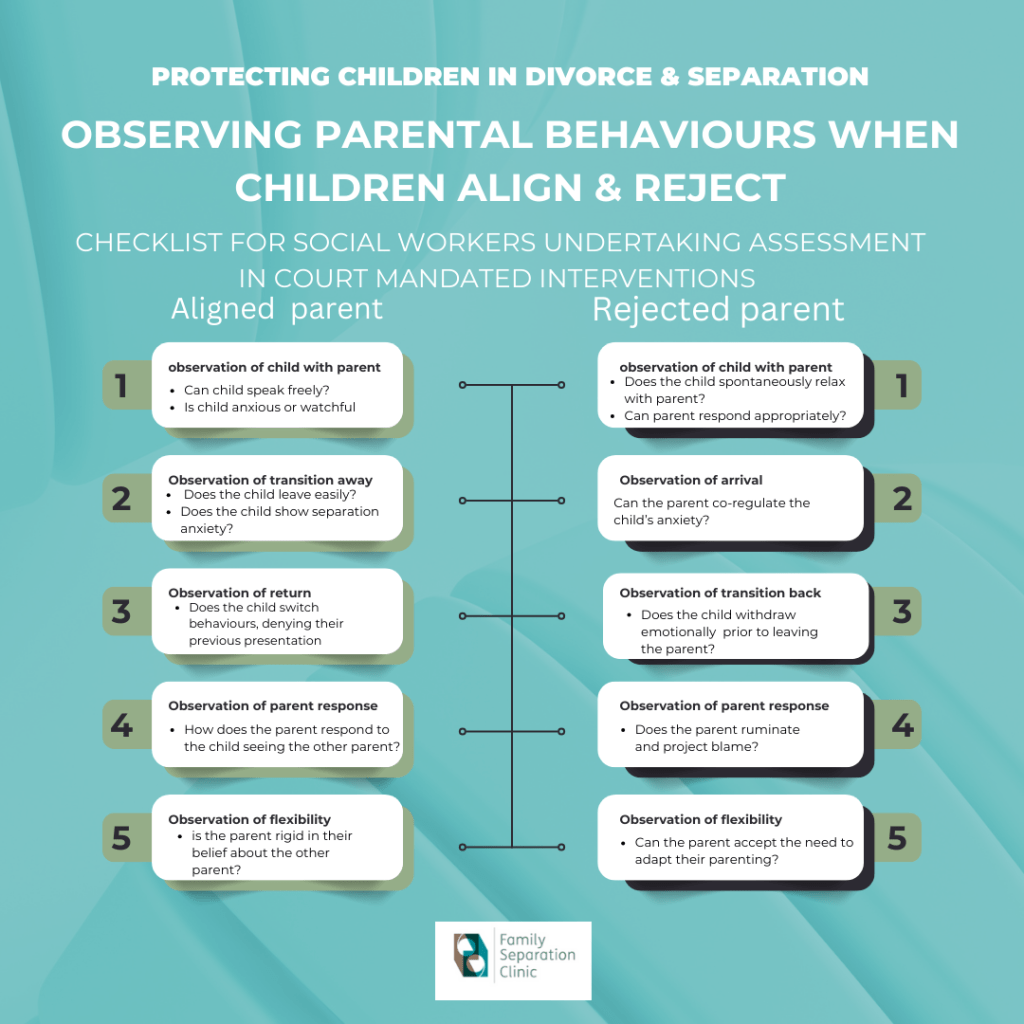

In our social work training pathways we do two things –

a) we enable social workers to understand their own internalised biases so that they can make better informed decisions based upon facts not feelings.

b) we help social workers to structure longer term observations of families where children display disorganised attachment behaviours in divorce & separation, so that they can effectively monitor parental capacity for insight and behavioural change.

Working with social workers who are trained in attachment theory, we provide a scaffolded lens through which parents can be regularly monitored using announced and unannounced visits at home and observed sessions between children and their parents. This scaffold, which combines social work principles with an object relations theoretical framework, ensures that both parents are scrutinised during such an intervention and data is gathered about parental capacity to provide safe care. This is the kind of work that we have done in the family courts in the UK, particularly in cases where there has been findings of serious harm by a parent against the children. It is a route used after removal from harm, to provision of kinship care by a parent who has been rejected by a child due to trauma bonding to an abusive parent. As such it enables decisions to be made which are safe in that both the abusing parent AND the parent who is in the rejected position are assessed and observed over time.

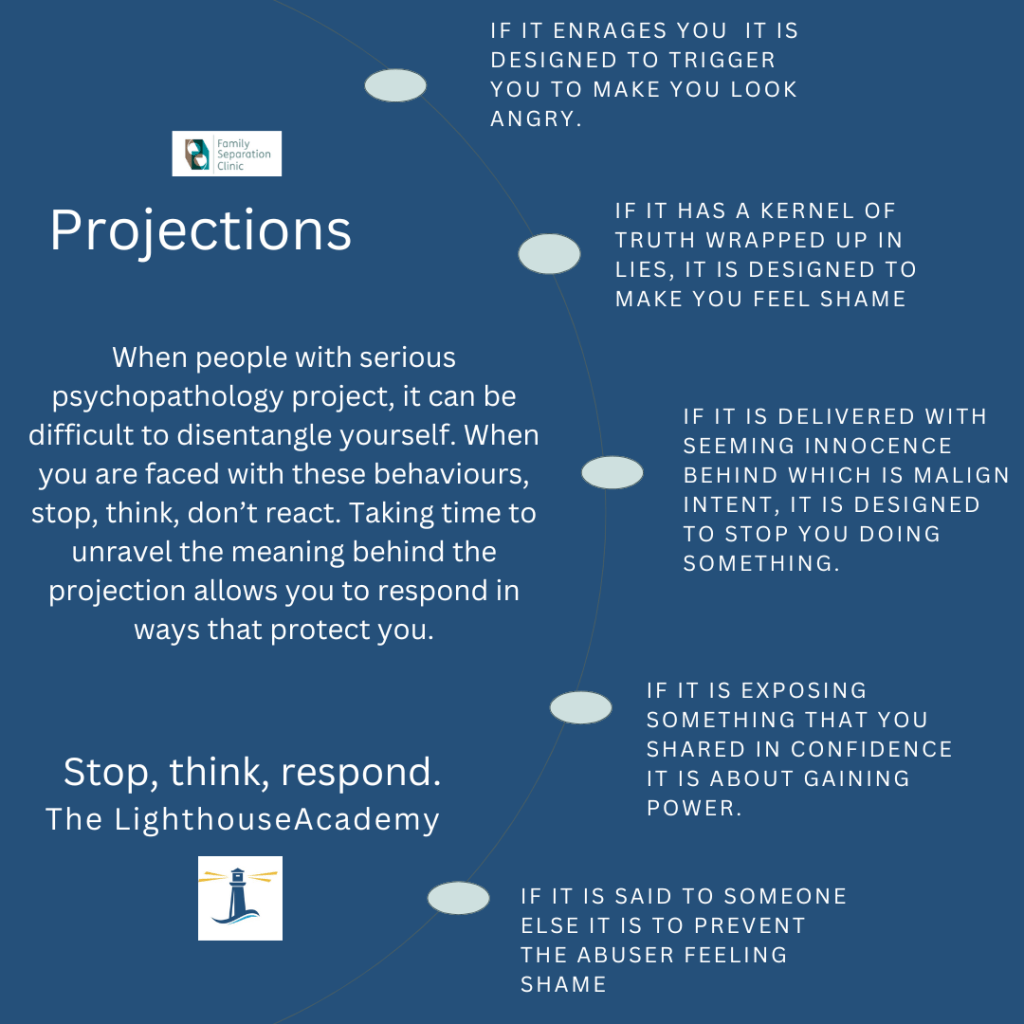

These kind of interventions are necessary because when children align with an abusive caregiver it is because they are being harmed out of sight. Like all abused children, strong alignment with an abusive caregiver is an indicator that something is happening behind closed doors. Sometimes what is happening is behind the closed door in the mind of the influencing parent because of the presence of powerful defences which act to prevent insight. In such circumstances, primitive defences are seen in a parent who projects blame and who is enmeshed with their child so that they do not experience difference between their own feelings and that of the child. Primitive defences are manipulative in nature and act to keep the defence in place. All family court professionals who work with this issue in children and their families will be aware of primitive defences, which can, if they are not understood, create a chaotic and fearful environment within the family home, as well as around the family being observed.

It is my view that the reason why we have not been able to stabilise and operationalise a consistent illumination of the harm which is being hidden in these cases, is because the field has become entangled with the very same projections which occur in the families we work with. In such circumstances, consistent and determined steps to illustrating, educating, guiding and supervising must be taken. Our social work training pathway does this in the UK and other countries in Europe to ensure that the hidden harm at home which is signified by children aligning with an abusive parent and rejecting the other, is better understood.

Family Separation Clinic News

The Clinic continues its supervision of a social work pathway in a case of two minor children trauma bonded to an abusive father in the Netherlands. The recent judgment in the case describes the steps taken by the Dutch Court to provide a child protection framework for the intervention, which is necessary when children are trauma bonded to an abusive caregiver, in this case a father who has manipulated his children to believe that their healthy mother is harmful to them.

Full Judgment

COURT OF MIDDEN-NETHERLANDS

Family and Juvenile Law

Location: Utrecht

Case Number: C/16/583423 / JE RK 24-1733

Date of Judgment: December 3, 2024

Ruling by the Juvenile Court regarding an extension of the supervision order

In the case of:

The certified institution SAMEN VEILIG MIDDEN-NEDERLAND, located in Utrecht,

hereinafter referred to as the GI,

Regarding:

[Minor 1], born on [birthdate 1] 2010 in [place of birth],

hereinafter referred to as [Minor 1],

[Minor 2], born on [birthdate 2] 2013 in [place of birth],

hereinafter referred to as [Minor 2].

The juvenile court recognizes as parties of interest:

[Mother],

hereinafter referred to as the mother,

living in [residence],

[Father],

hereinafter referred to as the father,

living in [residence].

1. Progress of the Procedure

1.1.

On October 31, 2024, the court received an application with annexes.

1.2.

The closed-door session took place on December 3, 2024. Present were:

- The father;

- The mother;

- [A] and [B] (behavioral scientists), on behalf of the GI.

1.3.

The juvenile court asked [Minor 1] for their opinion. [Minor 1] had a conversation with the court. During the session, the juvenile court summarized what [Minor 1] had shared. The attendees were then allowed to respond.

2. The Facts

2.1.

The father and mother share joint parental authority over [Minor 1] and [Minor 2].

2.2.

[Minor 1] and [Minor 2] live with their mother.

2.3.

On December 15, 2023, the juvenile court extended the supervision order for [Minor 1] and [Minor 2] until December 19, 2024.

3. The Request

3.1.

The GI requests the extension of the supervision order for [Minor 1] and [Minor 2] for a year and asks that the decision be made enforceable immediately. For the relationship restoration program by the Family Separation Clinic to succeed, it is crucial that the children stay with the mother and have no contact with the father or his network. To implement this relationship restoration program, the supervision order needs to be extended.

4. Positions

4.1.

The father has not opposed the extension of the supervision order. However, he disagrees with how the supervision order is being carried out and would like to see the children again.

4.2.

The mother agrees with the extension of the supervision order. She supports the current intervention methodology.

5. Consideration

5.1.

Based on the documents and the session, the juvenile court is of the opinion that the legal criteria mentioned in article 1:255 of the Dutch Civil Code (BW) have been met.

5.2.

Since the start of the Family Separation Clinic’s relationship restoration program, [Minor 2] has shown positive development. He seeks more closeness and rejects the mother to a lesser extent. It is important that the program continues so that this positive development can be maintained and the relationship with the mother can be further restored. Although [Minor 1] also made progress in the first weeks of the program, concerns about her well-being have significantly increased since late July. [Minor 1] comes home late every day and does not share who or where she has been. Additionally, [Minor 1] shows a lack of respect for authority and refuses her mother’s care. She rejects food prepared by her mother and does not allow her mother to wash her clothes. She also refuses to use items purchased by her mother. This indicates that she is not yet willing to improve the relationship with her mother. Given the progress [Minor 2] has made over the past few months, it is expected that, with guidance from the Family Separation Clinic and Pantser, [Minor 1] will eventually accept her mother’s care again.

5.3.

The juvenile court fully supports the relationship restoration program of the Family Separation Clinic and emphasizes that it is crucial for both children to remain with the mother and have no contact with the father and his family for the time being. In order for this treatment plan to succeed, the children must be protected from outside pressure to reject their mother so that they can again accept her as their primary caregiver. Only when both children no longer reject their mother can the possibility of resuming contact with the father be considered.

5.4.

The juvenile court therefore extends the supervision order for [Minor 1] and [Minor 2] for a period of one year. During the supervision period, the following goals will be worked on:

- The children will have unburdened contact with both parents.

- The children will learn to think more nuanced about situations and their parents.

- The children will accept the rules and boundaries set by the mother (when contact with the father resumes, this will also apply to the father).

- The children will be able to express their emotions in an appropriate manner.

5.5.

Finally, the juvenile court rules that [Minor 1] and [Minor 2] will no longer be summoned for any future hearings to meet with the juvenile court. Such meetings give the children a platform to express resistance to their mother and the policies implemented by the GI. It must be absolutely clear to the children, particularly [Minor 1], that there is no escape from the GI’s policy so that the chances of success for the relationship restoration program are maximized. Conversations with juvenile court judges interfere with this. The same applies to discussions with well-meaning but uninformed staff at child rights offices or complaint desks who are not familiar with the specific issues of these children.

6. The Decision

The juvenile court:

6.1.

Extends the supervision order for [Minor 1] and [Minor 2] until December 19, 2025.

6.2.

Declares this decision enforceable immediately.

This decision was given and publicly pronounced on December 3, 2024, by Mr. M.A.A.T. Engbers, Juvenile Judge, in the presence of Mr. P.S. Bamberg as clerk, and written on December 19, 2024.