Those who read regularly will be aware that I have long been a champion of the Early Intervention Project (EI) in the UK, a project which is designed to give guidance to the Judiciary on the matter of how much time a child should spend with each parent after family separation. This project has been tirelessly promoted by Oliver Cyriax throughout all of the time I have worked with separated families, (prior to which, as those of you who know my work from further back are aware, I previously worked with single mothers and their children). in 2002, with the support of the Judiciary, the EI was due to be implemented as a pilot project, until a clever little switch by civil servants from CAFCASS, ensured that a replica managed by Relate got the funding instead.

What happened next was legendary, thousands of pounds were spent by the government on a project which went on to work with a handful of families and the whole thing died a quiet death, pretty much as it was supposed to.

The idea of EI is an anathema to the people who were part of the stitching together of the social policy which surrounds families after divorce and separation in the UK. This is because EI would standardise expectations in the family courts of how a child is to be cared for by both parents after separation, increasing the power of mediation and leaving less room for argument. Where necessary, specialised mental health practitioners parents would guide and support parents and cases involving allegations of domestic violence and those intractable cases where a child rejects a parent would be triaged into a fast track system.

From where I am looking it is simple common sense, a way to remove the whole of the question of how children should be cared for after divorce and separation out of the ideological space it has languished in for too long. From where others are looking it is a curse upon women and we are already hearing the argument ‘every case is different’ and that this idea puts women at risk of ongoing coercive control and abuse. Fortunately, in the hands of a new President of the Family Division, EI in some form or other, seems likely to finally unpick the stitches which have prevented it from being successful in the past. What will get in the way however, is the ideological control of the space in which EI or any project with EI principles will be operated and it is worth examining this reality a little closer because of that.

Ideological beliefs are, as expressed by Louis Pierre Althusser, the French Marxist Philosopher, ‘the imagined existence (or idea) of things as it relates to the real conditions of existence‘. In this respect the imagined existence or idea being that men are born advantaged over women because of patriarchy.

When one approaches the idea of patriarchy (the key principle of feminism) from the perspective of understanding whether it is a real thing or not however, it becomes easy to understand how this is a theory of mind, not an objective truth. For example, if all men are born advantaged and all women disadvantaged, women born into positions of power, such as the Queen or other women with clear financial and power based advantage, would not exist. Neither would homeless men be seen on the streets and boys would not be killing themselves around the world at a far higher rate than girls. Our universities would be jam packed with young men and the young women would be absent in those places. The reality is that patriarchy, which refers to the way that society organised itself in some parts of the world, for some parts of history, is not an overarching super power which governs the life of men and women now. As such, it is a binary thought process – men advantaged/women disadvantaged which in the field of post divorce and separation care of children, does no favours to fathers and some mothers who become the ‘unintended consequences’ of feminist social policy.

The question then, of how children should be cared for after their parents divorce, is easily answered by saying that it should not involve ideology, which means that groups with the vested interest of promoting the rights of women and fathers groups which are formed in response to that, should not be left to toss the ball back and forth about what children need in this space.

(For people really interested in the history of social policy surrounding divorce and separation in the UK it is worth reading ‘An Exercise in Absolute Futility‘. by Nick Langford, ex of F4J, which curates the past in this field rather well. Whilst some have been systematically snooty about groups like F4J, the truth is that without them the issues facing fathers after divorce and separation would have remained buried. It was F4J who set the world alight in terms of raising from the unconscious the reality that dads matter too. Without F4J the movement to represent the needs of men and boys in the UK would not exist and those of us who have spoken up about equality in this arena would not have been able to do so. Those who systematically attack F4J whilst praising the work of the women’s rights movement, have a clear ideological agenda of their own and it is not about the needs of children).

Shifting the needs of children in the divorce and separation landscape away from the political football pitch of the mothers and fathers rights groups and into the arena of mental health has been a long term goal of mine. In my work over the past two decades, I have been witness to how the women’s rights groups misrepresent the needs of children after divorce as being about money and their mother being able to control outcomes in terms of relationships with fathers. The mental health of children who have suffered attachment disruption through divorce and separation has been completely ignored in this landscape and those of us who have spoken about it have been either ignored or ridiculed. In my work as advisor to the Coalition government in 2011, I watched as again and again the use of the belief that men were inherently dangerous, scuppered all plans to bring a greater father involvement into the lives of children of divorce. I sat and watched as the government funded charities such as Women’s Aid, Relate, Gingerbread and One plus One, banded together to ensure that the proposed reforms were watered down to mean absolutely nothing different. I am watching again now as the conversation around recent speeches given by the incoming President of the Family Division about the idea of intervening early in private family law cases, raises those same red flags from feminists which have always been seen waving above the parapets of the tightly stitched social policy which surrounds divorce and separation.

The gendered control of the divorce and separation landscape in which children are forced to navigate abrupt changes to their lives must stop if we are to make any difference to the lives of future generations of UK born and raised children. The UK has the highest rate of intergenerational family breakdown in Europe and the manner in which the lives of children are overlooked in favour of their mother’s needs contributes enormously to this in my view. I am already reading, from Women’s Aid for example, about how women’s needs are overlooked in favour of those of fathers in the family courts and we can expect these narratives to be raised to an ear splitting degree in the coming months should Sir Andrew McFarlane go forward with anything like the EI to set new standards in the management of disputed cases in divorce and separation.

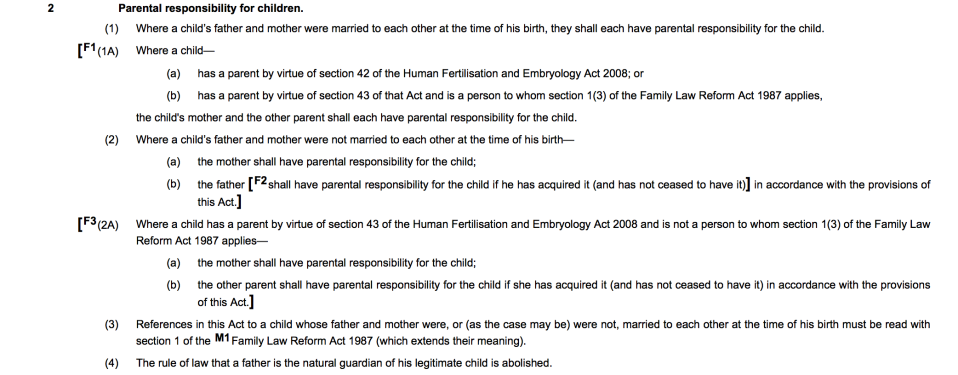

Make no bones about it, the unpicking of the tightly stitched social policy around divorce and separation will not come without a fight and that fight will be by fair means or foul. With government funded charities heading coalitions which ostensibly appear to be in support of shared parenting but in reality are anything but, the women’s rights agenda, which is to give maximum control to mothers after divorce and separation, will continue to be manifested everywhere it is possible. When ideology wrote the very social policy which governs the landscape, there cannot be anything other than a drive to maintain that control, it is stitched into the very fabric of the Children Act in ways that are beyond the comprehension of most. Who knew for example that the rule of law that the father is the natural guardian of his legitimate child, had been abolished? It was and it still is and here is the evidence at section 4 under Parental Responsibility, for those who need to know. Against this backdrop, it is little wonder that the fight to assist children in the post divorce and separation landscape has been such a tough one. The needs of children have been seen as indivisible from those of their mothers for decades and the needs of children for a relationship with their father has been seen as virtually non existent. Where there has been a begrudging acknowledgement of this, the strap-line ‘children should have a relationship with their father, where it is safe to do so‘ has been tagged onto every single government initiative to create change, over the whole time I have worked in this field. The assumption being that men are inherently dangerous to their children and therefore caution and great care should be taken when making post separation arrangements which involve fathers. In one government initiative I worked on, which was designed to help mothers and fathers work together after separation, the strap-line was plastered so heavily across every document and every message to families that I gave up in the end. Who in the world could possibly imagine that mothers would work with fathers when they are encouraged and exhorted to think of them as dangerous and incentivised into not doing so.

Against this backdrop, it is little wonder that the fight to assist children in the post divorce and separation landscape has been such a tough one. The needs of children have been seen as indivisible from those of their mothers for decades and the needs of children for a relationship with their father has been seen as virtually non existent. Where there has been a begrudging acknowledgement of this, the strap-line ‘children should have a relationship with their father, where it is safe to do so‘ has been tagged onto every single government initiative to create change, over the whole time I have worked in this field. The assumption being that men are inherently dangerous to their children and therefore caution and great care should be taken when making post separation arrangements which involve fathers. In one government initiative I worked on, which was designed to help mothers and fathers work together after separation, the strap-line was plastered so heavily across every document and every message to families that I gave up in the end. Who in the world could possibly imagine that mothers would work with fathers when they are encouraged and exhorted to think of them as dangerous and incentivised into not doing so.

And so here we are in 2018 with the possibility of EI once again on the horizon and the hope that children’s needs in the post separation landscape might truly be taken seriously instead of being rolled up and disappeared into the needs of their mothers. Here we are again, hoping that this time a framework to stop the unintended consequences created by feminist social policy, (which leads to mothers being pushed out of their children’s lives by alienating fathers as well as fathers being airbrushed into meaningless shadows on the far margins of their children’s peripheral vision,) will be created.

As an aside, I should say a word here about the unintended consequences of feminist social policy and alienated mothers because it is a little understood reality. The feminist battle against the concept of parental alienation is focused upon the notion that parental alienation is only ever used by father as a method of control over mothers. It is dismissed as a real thing and denied by Women’s Aid. In denying the existence of parental alienation however, these bodies overlook the mothers who are being alienated from their children by fathers who use coercive control. These women are the ‘unintended consequences’ of feminist social policy. They are ignored and denied because parental alienation is ignored and denied. And yet they are suffering text book coercive control after separation which is erased from the consciousness of the very organisations who should be helping them. Meanwhile, the mothers who do alienate their children (and have them removed because of that), are championed as being the innocent victims of fathers using parental alienation as a false allegation. This is what you end up with when you use ideology as a foundation for family services. Huge gaps where support should be and a focus on the perceived idea of what coercive control looks like instead of the reality of what it is.

EI is a framework which could deliver very different outcomes for children of divorce and separation where parents cannot agree arrangements. It contains within it, the principles which already exist in the Children Act and each case will remain different and unique but governed by a new set of expectations. Triage services will ensure that cases of domestic violence and parental alienation are fast tracked and heard early and there will be no languishing in the system for years on end to get to a place where it is too late to do anything. EI ensures that childhoods will not be wasted in litigation, mothers will not be alienated from their children and fathers will get a fair hearing in which their children’s needs for time with them are properly recognised. Anyone who suffers coercive control will have their case properly tested and safeguards will be inbuilt to ensure that no-one has to live with the consequences of an abusive relationship.

Sounds like a utopian dream? Remove the ideology from the social policy and it is plain and simple common sense.

Just don’t expect it to come about without a monumental fight.

By way of another perspective on this same matter, here is a comment piece from NAAP published today and giving us more thinking about why it is so vitally important to get the issue of how to meeting the needs of children in divorce and separation right out of the parental rights arena and into the space it properly belongs in which is mental health.

EI will be discussed on days one and two at the European Association of Parental Alienation Practitioners Conference in London on August 30/31st 2018 as a method of triaging cases of PA into specialist treatment programmes.

Book tickets for the conference here.

Good post Karen –

by way of a supplement – this useful quote is extracted from a speech given by Lord Justice McFarlane, President of the Family Division, at the Families Need Fathers Conference, 23 June 2018 where he also talks about EI

“From my experience as a first instance judge, albeit now more than 7 years ago, I readily accept that in some cases a parent can, either deliberately or inadvertently, turn the mind of their child against the other parent so that the child holds a wholly negative view of that other parent where such a negative view cannot be justified by reason of any past behaviour or any aspect of the parent-child relationship. Further, where that state of affairs has come to pass, it is likely to be emotionally harmful for the child to grow up in circumstances which maintain an unjustified and wholly negative view of the absent parent.”

LikeLike

Hi Karen

The new president has certainly made a lot of the right early noises but when with each passing day I hear a new story of the Alice in Blunderland world that is the family justice system. My heart sinks at the reality of the task Sir Andrew faces. He really does have a huge mountain to climb.

The early signals are that he wants the judges to take ownership of the early interventions scheme. But, i am afraid that the enormity of that task cannot be understated. In reality we still have far too many absolutely dreadful judges who are grazing happily in the meadow of the lower courts. Lately, I have seen a disturbingly high number that still struggle with ancient concepts of law like Magna Carta which 800 years ago was supposed to have consigned arbitrary justice to the history books. Sadly, these simple concessions to human decency are being flaunted daily by bloated egos in the name of justice. At NAAP and DADS we deal daily with the fallout in the shape of broken and suicidal parents for whom the system has been just too much for them to bear.

This is what life is like at the coal face. It is not pretty and sadly arbitrary justice and abuse of process is alive and well, literally as we speak, in a family court not very far from where any one of your readers live.

LikeLike

CG

In his opening speech to FNF Lord McFarlane says he is going to spend at least a year talking to all interested parties, Cafcass, the judiciary, FNF and Women’s Aid amongst others and then he is going to reach a conclusion.

Sounds like history repeating itself to me.

In other words he is going to spend another year discovering what we already know.

McFarlane is a well-practiced speaker. He makes a point of buttering up FNF telling them how wonderful the organisation is and what a great source of reliable accurate information they supply, then he says he is going to listen to Women’s Aid and deliver exactly the same sentiment so that they too feel like they are winning the day, and then he will do absolutely nothing.

He will continue to pit mothers against fathers as if this is some kind of tug-of-war and fail to recognise that what we are dealing with is people’s mental health. The mental health of children, who will continue to be alienated, damaged or transferred to alternate parents chosen by the State. The mental health of fathers who in their quiet inimitable way fluctuate between despair, anger and self-destruction and mothers whose sense of loss, abandonment and worthlessness and shame is overwhelming.

Which is why we need to organise and demonstrate an alternate system that works

LikeLike

Sadly I’m all too aware of the wide-ranging and multi-affecting mental health repercussions of PA.

For a very long time I laboured under the misapprehension that if only I could find the right phrase, the right quote, I’d be able to transformationally educate and illuminate those in power, and with power, in the situation within which my family has suffered, and continue to be subject to. That, in my case, was an impossible quest, and now a lot of time has gone by, and years have been lost, and we’re beyond that point.

However, I do feel that quote sums up PA quite simply, without apportioning divisive blame by the use of the words ‘either deliberately or inadvertently’, whilst focussing on the ‘unjustified’ nature of the sustained negative view. And Lord Justice MacFarlane’s position makes this a weighty quote, and it may be helpful to someone, somewhere, in their own journey towards understanding.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Madison Elizabeth Baylis.

LikeLike

Bless you flower, Godspeed. Xx

LikeLike

Early Intervention sounds good to me. Abuse of women is such an emotive topic that it seems to infiltrate everything and distract from matters like Mothers (or Fathers) abusing children. Womens Aid is an outmoded name. It should be Abuse aid. Because there are also abused men out there and not all women are safe parents. History is full of them. Indeed it makes my head spin at the enabling of abuse by the view that children belong with their Mothers (and I do realise there are some alienated Mothers as well) who will protect their children. As an example a Mother who neglects a child for years, leaving them with various people so they then hardly know her, can later claim her motherly instinct is the reason the child “doesn’t want to go”. I was informed by a relative – a specialist in working with children – that there is a bond between Mother and child that is like no other and that is why the Mother is the most important thing in a child’s life. If this is what they are teaching in medical school it needs updating. Is that also part of the feminist model? I am not denying the bond of giving birth (which does not happen in all cases and some Mothers don’t bond with their children whatsoever) but it denies the incredible bond a Father can have for a child – and in my opinion it is equally as strong. Sorry gone off topic a bit!

LikeLike

Basically saying I agree it should not be about gender. There are good people, bad people, slightly good and slightly bad, and dangerous mixed up people – regardless of whether they are male or female or even biological parents. One thing I find strange is that step parents tend to be left out of the mix when a step parent can sometimes be the one holding it all together and the child may also have a strong bond with them.

LikeLike

Got to see, up close and personal, how Andy Mc operates over a period of 2+ years (between 2007-09) and 12 to 15 court hearings……..’never say never’ but remember not to hold your breath. How was that for “fence-sitting”?🙈😊🤔😡

LikeLike

Parental alienation……an issue for mental health

The most successful treatment of psychosis in “western type societies” has been to use an “early intervention” approach.

Dr. Jaakko Seikkula has nearly 30 years’ experience using early intervention approaches with his CAMS (community and mental health services) type teams to avoid the onset and crippling effects of schizophrenia.

The approach is based around the family dynamic and views psychosis as a socio-psychological phenomenon.

https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=open+dialogue+youtube&&view=detail&mid=84EB664FD7EE9ED451F684EB664FD7EE9ED451F6&&FORM=VDRVRV

Whilst I hasten to add psychotic episodes are not the same as the delusional experience of the child during parental alienation, both require the quick intervention of expert family assistance.

LikeLike

thank you NGB I will take a look at this, I am always looking for best practice in this field, this looks interesting indeed. K

LikeLike